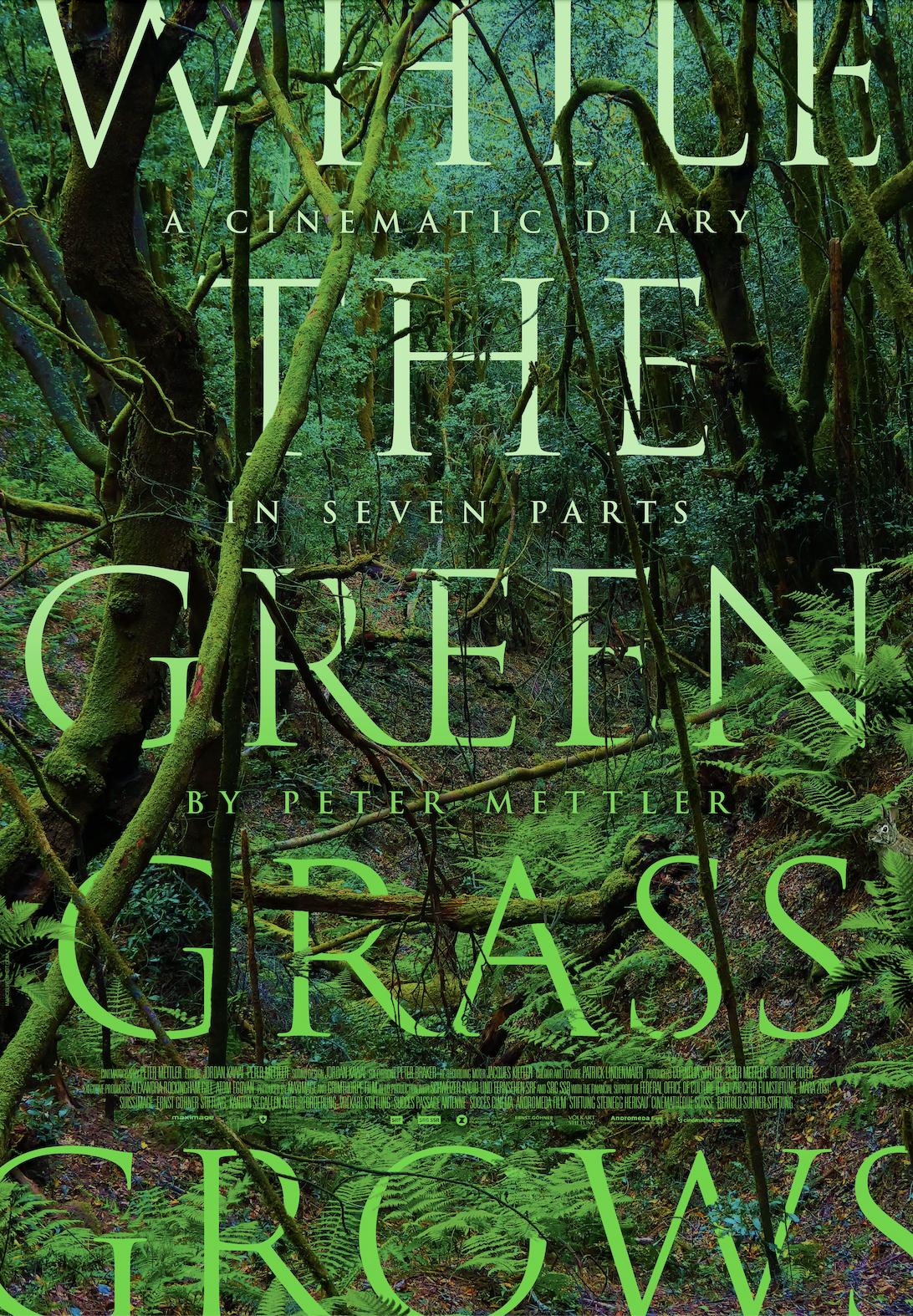

While the Green Grass Grows: A Diary in Seven Parts

a film by Peter Mettler / Canada / Switzerland/ 2025 / 420 minutes

A chronicle of the miracles contained in everyday things and occurrences, this most ambitious work from award-winning filmmaker Peter Mettler elevates the diary into the realm of visionary cinema. His meditative approach and ever-searching gaze create a generous space to embrace the fragility and profound nature of relationships, where reflections on the human condition and our environment flow together in a stream of consciousness.

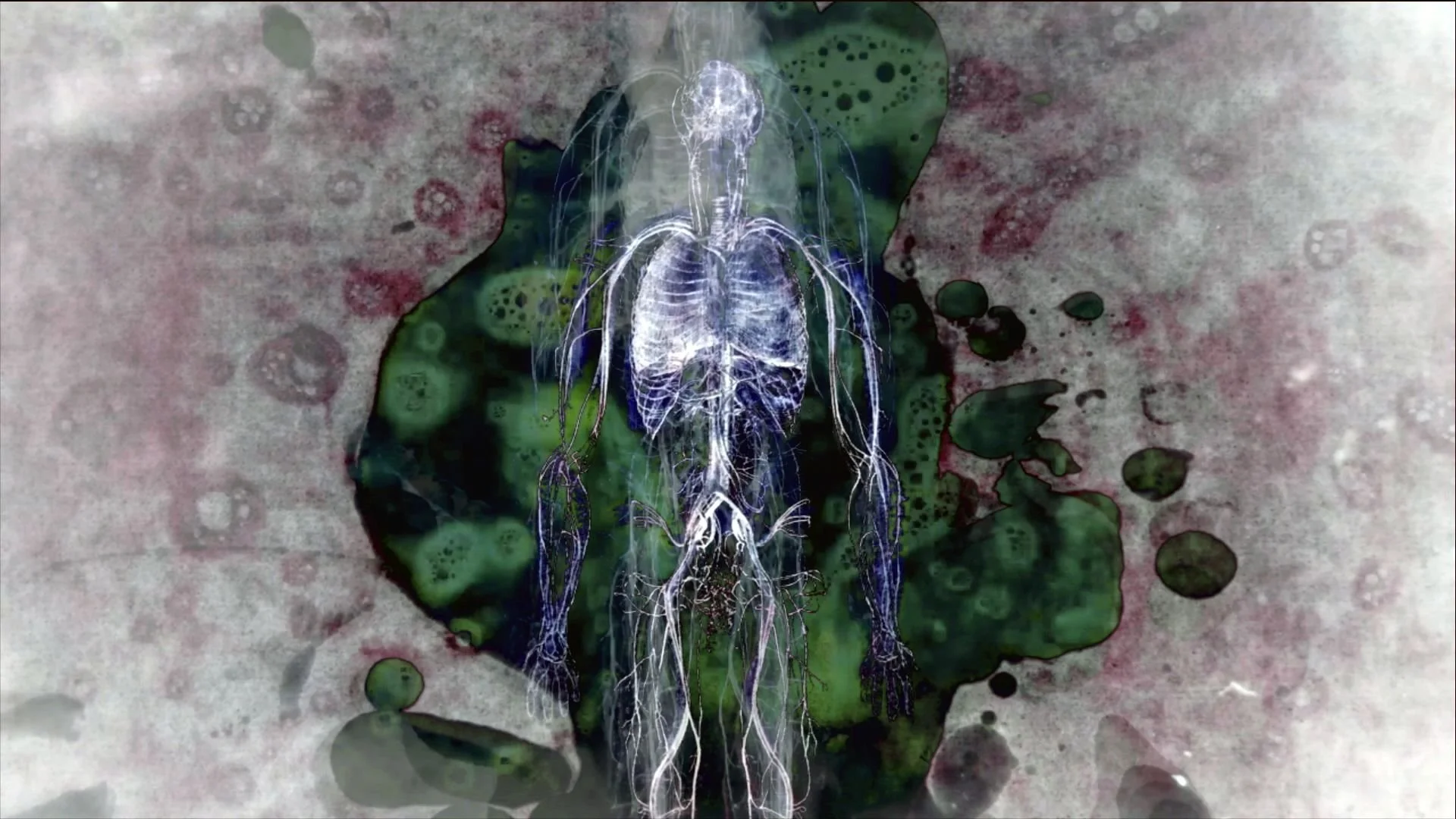

Alternately tragic and comic, philosophical and poetic, Mettler‘s ebullient diary, filmed over three years, combines personal conversations, family history, memoir, homage, and love, while its aesthetic is laced with psychedelic and experimental imagery and sounds that enhance its trance-like feel.

While the Green Grass Grows: A Diary in Seven Parts is a work of maturity, rigour, and startling intimacy that interrogates our collective destiny with grace and wonder.

Block 1: 196 min

Part 1 - HERE IN THIS WORLD (77 min)

Part 2&3 - MY GRANDMA WAS A TREE + TRUTH AND CONSEQUENCE (71 min)

Part 4 - FREDDY’S DIARY (48 min)

Block 2: 223 min

Part 5 - OJO DE AGUA (77 min)

Part 6 - THE RIVER AFTER (86 min)

Part 7 - TINY SPECK (60 min)

CREDITS

Written & Directed by Peter Mettler

A Grimthorpe Film and maximage production

Produced by Cornelia Seitler, Peter Mettler, Brigitte Hofer

Executive Producers Alexandra Rockingham Gill, Atom Egoyan

Cinematography and Location Sound Peter Mettler

Editing Jordan Kawai, Peter Mettler

Sound Design Jordan Kawai

FEATURING

Featuring Julia Mettler, Alfred Mettler, Peter Mettler, Mara Züst, Gass Rupp, Jeremy Narby, Grant Lacquement, Samara Chadwick, Lola Tartane, Lazaro O Lemus, Fernando Birri, Violeta Mora, Julia Rizzo, Evelio and Laura, Omar Perez, Eamon MacMahon, Lyana Martins, Yanis Careto, Cecilia Cores, Tony Spencer, Troy McClure, Alexandra Rockingham Gill, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, Becca Blackwood, Krstivoje Mitric, Dr. Peter Brugger, another Peter Mettler

Filmed on location in and around Kantons of Appenzell AI & AR, Switzerland, La Gomera, Spain, Tonkiri, Whitemouth River, Manitoba, Canada, Climate protest march, Toronto, Canada, On the road between Toronto Canada and Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, Bandalier, New Mexico, Sedona, Arizona, Killarney Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada, San Antonio de los Banos, Cuba, Havana, Cuba, EICTV, Cuba, Greater Toronto Area, Canada, Toronto Airport Quarantine Hotel, Canada, Säntis, Kantonsspital St.Gallen, Rehazentrum Valens, Tamina Schlucht, Rheinfall, Switzerland

DOWNLOAD IMAGES & POSTER

Electronic press kit

Download Peter’s Curriculum VitAE

Download Peter’s SHORT BIO

Download Peter’s Portrait

For further info please contact info@maximage.ch.

AWARDS

2025 Student Jury Award, Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival

Jury statement: The jury recognizes a film that, in today's fast-paced world, reminds us of the power of standstill, silence, and the present moment. With courage and creative freedom, it leads us to reflect deeply on time, memories, and our place in the world. The award goes to While the Green Grass Grows: A Diary in Seven Parts by director Peter Mettler.

REVIEWS

“Years in gestation, this magnum opus from Peter Mettler, one of our most individual, poetic and inquiring filmmakers, who also shot the gorgeous imagery, promises to be a probing, reflective reverie full of questions on our puzzling and contentious relationship to the natural world that also traverses deeper existential questions, prompted by aging parents, around life, death and memory.” — Piers Handling, former TIFF CEO

“A gorgeously made physical and metaphysical journey by Canadian maverick director Peter Mettler that tackles life and death issues with style and care — in a mere seven glorious hours.” — Marc Glassman, editor of POV magazine and critic for the New Classical 96.3 FM

PRESS & INTERVIEWS

“While the Green Grass Grows Review: Or, the Endlessness of Time”, POV Magazine, September 8, 2025

DIRECTOR’S NOTE

I want to let life make this film. The life I encounter as a filmmaker, mingling and travelling with others, both family and strangers. I, as just a medium with a recording device that observes and sometimes comments as things unfold.

We all yearn for something. Something elsewhere… or perhaps just for simplicity and presence in this world so deeply layered.

One thing always leads to the next. That is the perpetual motion, the never-ending transition that gathers meaning and interconnection as the focus of our own lives moving forward – or is it better to say outward – gathering density of experience, associations, karma.

I choose the path of least resistance, like the way of water, keep flowing. It takes me everywhere and presents to me the cycles, not only of matter but of life and death itself.

I meet my neighbours, the people, and the animals, traces of ancestors, trips down rivers and across continents, through culture with their particular longings for greener grass. Canada, Switzerland, America, Cuba - the names of borders within which I see people and details of the everyday.

A talking crow on a pole, a glistening doorknob in the sun, ice forming and melting, giving way to abundant fresh life. A Jeremy Narby, an Alexandra Rockingham Gill, another Peter Mettler, a nurse, a doctor, a Bosnian, many more people, and a group of filmmakers in a film school, documenting the imagination as well as the world outside of our perception known as Cinema Verité.

A film created as a parallel technological universe of culture and humanity. Now, more than ever, everything we do contributes to the character of the future.

And then my dear father, Freddy, dies - and I write cinematic love letters to him and Mom. The film is my grieving and helps me to share with its future viewers what it is really like to lose your parents, and how it can be beautiful too.

The Virus comes and challenges us to learn more about ourselves, how to remain connected and alive in better ways. I too must go to a hospital, getting up close with that unknown darkness we all wonder about.

The cycles are what we are and there is always cause to celebrate the miracle. Always room for being in a state of AWE. And now we have our memories bolstered by technology taking in this life through recordings, like the very one I will present to you.

We are born of the cultural riches of those before us: Thich Nhat Hanh asks – before that day which you call your birthday – where were you?

2025 - I survive another year here on earth, synchronicities abound as our film will have its world premiere on my birthday day.

Let’s keep the Green Grass Growing - All Around All Around

Peter Mettler

A CONVERSATION WITH PETER METTLER

The following is a condensed excerpt from José Teodoro's forthcoming book Nothing But Time: Conversations With Peter Mettler On Life and Cinema.

Take me through the genesis of While the Green Grass Grows: A Diary in Seven Parts.

It sprung from the desire to go into exploration mode again: you have your themes and strategies and go out into the world and discover things. That was my main motivation, wanting to work like that, alone or with just one or two people. Meanwhile, I thought the adage “the grass is always greener on the other side” could serve as a guiding query. We always want something else, something more, something deeper: this is part of how we evolve.

Your mother died just before you began, and your father died while filming. Would you say filmmaking became a coping mechanism for grief?

Better than a coping mechanism, it was a way to embrace what was happening. My father's dying became a wondrous thing. I remember telling him, "Everything is the way it should be. You're going where we all go, whatever that is." One morning, while visiting my father in hospital, I saw a pregnant woman coming to give birth. I was reminded that one phenomenon is just the opposite end of the other. Alongside the loss, the change, the management of death, it still felt right. It was even inspiring, the privilege of having parents who'd lived long lives, the privilege of having ended on good terms, of being able to spend time with my dad after my mom passed. And to be making a film along the way.

In Part One, in that scene in the attic, your friend speaks of the importance of telling the right story at the right time.

To me, that's just part of observing, instead of imposing. When you get to the end of the filmmaking process, you look at the story and go, "How amazing that these things happened while filming and added up the way they did!" But that’s how life goes. The key is that someone was paying attention. I'm not doing much except going with the flow.

Part Two finds you drifting down a river with [anthropologist-author] Jeremy Narby. How did that come about?He invited me to a retreat. I don't remember whether I proposed a shoot or if I simply had my camera and we started talking. I'd often thought about doing something with Jeremy. We're friends and I like his ideas. He's a great orator. We'd already done Yoshtoyoshto, our live event where I perform improvised image mixing, Franz Treichler [of The Young Gods] plays music, and Jeremy speaks. So bringing him into Green Grass seemed natural.

Was your canoe ride undertaken with a particular intention?

I was interested in this question about whether technology is part of nature—which proved ironic, since my camera falls in the river when we come back to shore. But our topics of conversation drifted, along with the canoe, to the presence and power of plants, life without humans, and the importance of sharing knowledge and viewpoints.

There's an incredible moment of sharing in Part Three, with Grant, who you met while visiting Truth or Consequences, New Mexico.

Grant was at a screening of Gambling, Gods and LSD at a festival there and I happened to bump into him the next day. I enjoyed speaking with him and asked to film him at his home. He turned out to be incredible in the way he articulated himself on camera, having had a profoundly shocking experience that changed his perception of himself and his world.

I love his phrase, "My heart slammed into the mountain."

Grant has a particular way with words. He's concise. He's an ascetic, as you see in the film. There's almost nothing in his room, just a photo of a Swami on a mountain, a couple of books, and ten white tshirts. As he explains, he'd lived out of his van, so his life is reduced. And he clearly spends a lot of time in nature.

Part Four unfolds entirely in nature, at Killarney Provincial Park, Canada, where you went with your father, Freddy, a year after your mother's passing.

Throughout our lives, I would've liked to have spent more time with my dad, just the two of us. This seemed like a chance to realize that. I was trying to take him to places, show him nice things, inspire him, talk with him. I told him Killarney was a place I loved for its wilderness and beauty.

Let's talk about Freddy's diary, which you examine in this episode—and which I adore.

Freddy kept diaries going back to when he first came to Canada. What always amazed me about them is that they were primarily factual. There was little expression of how he felt. As you probably notice in the film, the books he used as diaries would have, say, five years worth of September eighths on a single page.

This layering of things that happened on a particular date over several years: it's like a geological illustration. I love that Freddy's diary is now part of Peter's diary. Did you tell Freddy you were making a diary film?

There's some conversation in the film about that. I ask him, "What do you think about making a film where you just go out and explore and document what happens?" And he says, "Isn't that just how life goes?"

Did your parents ever protest against you filming them?

Freddy's resistance consisted of, "Why are you're filming? This is very boring." [laughs] As for my mother, I think she liked it. She could ham it up, make faces. It actually bonded us. She even took up photography in her 80s. When I pointed the camera at the two of them, they'd often start dancing.

What do you do when people point cameras at you?

Weirdly, after all these years, I still feel the poignancy of the recorded moment. That's the base feeling of recording, whether I'm filming a forest or a person. I actually find it hard to film a person if there's not some rapport there. If somebody points a camera at me, I might become a little self-conscious. It's a moment that will contribute to a parallel reality, the one that exists in a recorded medium for however long it lasts.

Let's talk about that with regards to Part Five, which is set in Cuba and is partly about filmmaking itself.

I went to Cuba to lead a workshop with other filmmakers at EICTV, the International School of Cinema and Television, where I offered the "greener grass" theme as a starting point. The workshop lasted three weeks, but I wound up staying longer and working on my own film. I collaborated a lot with Julia Rizzo, one of the participants, in quite a freewheeling, intuitive way that mixed documentary and performance, only realizing during editing that one of the school’s founders, Fernando Birri, worked in similar ways.

The end of Part Five is dreamlike. Narrative and geography become unmoored: we're transported from the Caribbean to a snowy forest and back again. I love that the itinerary is left mysterious.

We discussed those geographical shifts a great deal during editing. I'm curious to see how it will be with an audience, as things move into streams of consciousness at times. I really like those segues into different realities—which are also, to my mind, documents of how we think and feel.

Part Six involves both the onset of the pandemic and Freddy's passing. Did you have reservations about filming him toward the end?

I was with him for nine days in hospital. I read him texts. I played him music. I put photos at his bedside, so though he often seemed to be in another world, when he opened his eyes, he could see images of people who love him. I explained that filmmaking is something like a religion for me. I ultimately thought it was right to keep filming. All the things that had happened leading up to that point supported this decision. It’s interesting how capturing real death remains a taboo in film. We all go through this, but it's not talked about much. I considered it thoroughly and I believed it could be spiritually nurturing for an audience. It came from a place of love.

I sense a new level of formal exuberance to your filmmaking. Something I really responded to were the diptychs in Part Seven, in which, among other things, we witness your recovery from a mysterious illness.

In that episode, the neurologist Peter Brugger talks about juxtaposition and building meaning from our experience. So we decided to create flashbacks. I asked [editor] Jordan [Kawai] to create a set of juxtapositions—or diptychs, as you call them—out of moments that came earlier in the film. It was one of the rare times in editing where something was drafted, I looked at it, and said, "It's perfect." Then there was the water diptych, which was made using a Plexiglas ball that Patrick Lindenmaier created. Besides being a skilled image-maker who colour-timed the film, Patrick's a scientist and a crafty guy, so he made this ball with two cameras in it, one looking forward, one looking back. This ball going down the water relates to following the river, the future and the past, while Brugger talks about coincidence and simultaneity. It all seemed to fit.

These diptychs speak to the way the mind can hold two things at once, a memory alongside the perception of the present.

I was interested in the double perspective on a single moment, the way juxtapositions, like edits, generate meaning. Also, because it's a recap of an individual's diary, a survey of my life over a few years, these diptychs allow you to see that life or memory is made up of components in which we try to find narrative. To reduce things to a single linear story is to deflate them. Because myriad things happen and affect each other. This extends to everybody we meet.

We talked about the film as a way of processing grief. What's the feeling now? You spent three years filming, not to mention all the time devoted to conceiving, editing, and completing it. Is there any grief about it being finished?

No grief. Just relief. [laughs] And excitement, actually. I feel like I’ve passed through a couple of life’s essential passages, having engaged with my parents' and my own mortality. I look forward to what comes next and experiencing the film with an audience. I can’t wait to meet them.